What they are

Intelligence requirements were, strangely enough, one of the last things I learned about when I started learning how to perform cyber threat intelligence(CTI) for my organization. I had goals for myself, but nothing in an organized fashion. Intelligence requirements can be called several names and even broken into more granular categories. To keep things simple for this blog post, I will refer to them as Priority Intelligence Requirements(PIRs). Borrowing from the Reliaquest post on PIRs, they are crucial in making the intelligence life cycle go around. Requirements are used to:

- Provide direction for an intelligence analyst to gather and collect information.

- Requirements define the required resources and gaps in capabilities for collection management purposes.

- Requirements determine the end product that will be produced and whether the end user will be satisfied with the results.

To sum it up in my own words, PIRs are the goals of the intel team. They are the questions the organization needs to answer. By answering the questions, you augment other teams by making them more efficient and providing them with situational awareness to protect the organization. CTI is the “targeting computer” in X-wings, if you will catch my reference. The examples I’m going to go over are more skewed toward smaller intelligence teams for small to medium-sized businesses(SMB).

How do we make them

Creating good PIRs can be a complex/long process depending on who you are supporting, what their needs are, and how well you know your organization. The first step should be to understand your organization from a business and technical standpoint. Understanding what your organization does, what assets they value the most, and what your secret sauce is can help you understand what intel people need.

Talking to your consumers will provide good information on their needs. Ask them what keeps them up at night, what type of decisions they are making in their roles, and what the priorities of each of those decisions are. Depending on the consumer and the experience of your organization, people may not know what they want or what CTI is capable of providing. Knowledge of CTI will vary depending on roles and departments. Still, having that initial conversation will allow you to scope the situation and, even more importantly, learn what they think is high risk. This conversation is also an excellent time to understand how they would like to receive the intelligence that you will be providing. Via automated lists, emailed reports, blog posts, or automate the consumption into the tools they use.

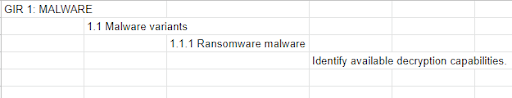

Now that you know what type of information your organization needs, think about if and how you can collect the information needed to fulfill the requirements. Once you have that information, it is time to start putting the keyboard to excel spreadsheet. There are a couple of different ways to do this. Once again, it all depends on your organization and how much work you want or need to do. For larger organizations with a dedicated team, check out RedHat Infosec post on creating PIRs and Intel 471 cyber underground general intelligence requirements handbook. Their methods are much more thorough but require much more work and are geared toward providing a large amount of intelligence. Working for an SMB, I found this information useful but not necessarily needed for my organization. I was one man jamming intel and didn’t necessarily have time to recreate their steps. I do agree having requirements and sub-requirements is an important notion. Imagine a Russian nesting doll of requirements. An example would be Malware:1 < Malware variants:1.1 < Ransomware malware:1.1.1 < Identify available decryption capabilities.

This example is excellent if you have the resources to provide and focus on the finer details of a requirement. Most SMBs, I don’t think, will need to get that detailed or have the bandwidth to.

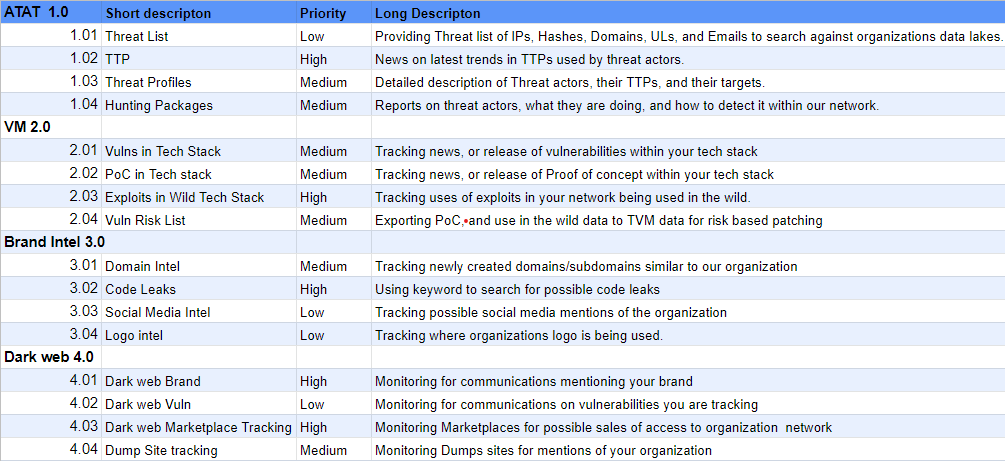

Wadingthru PIR Frameworks

My less organized way is in the example to the right. I List several different categories. Adversary Tactics, Activities, and Techniques(ATAT), and Vulnerability Management(VM) are the two main PIR categories.  You shouldn’t abbreviate anything for public consumption because it may create confusion. I just thought ATAT was too good of a Star Wars reference to pass up. My quick and dirty Intel framework requires an Intel category with a numerical ID, the requirement(short description), Priority, and long description(detailed requirements). Each short description contains an ID corresponding to the category. The short description plays the role of the general intel requirement, whereas the detailed description explains the different sub-requirements. I found this easier to read and understand for people unfamiliar with CTI. I used a priority scale of Low, Medium, and High since I was not getting too in-depth. It gets the point across more straightforwardly and doesn’t require math formulas. These priorities were usually set by the team that needed them.

You shouldn’t abbreviate anything for public consumption because it may create confusion. I just thought ATAT was too good of a Star Wars reference to pass up. My quick and dirty Intel framework requires an Intel category with a numerical ID, the requirement(short description), Priority, and long description(detailed requirements). Each short description contains an ID corresponding to the category. The short description plays the role of the general intel requirement, whereas the detailed description explains the different sub-requirements. I found this easier to read and understand for people unfamiliar with CTI. I used a priority scale of Low, Medium, and High since I was not getting too in-depth. It gets the point across more straightforwardly and doesn’t require math formulas. These priorities were usually set by the team that needed them.

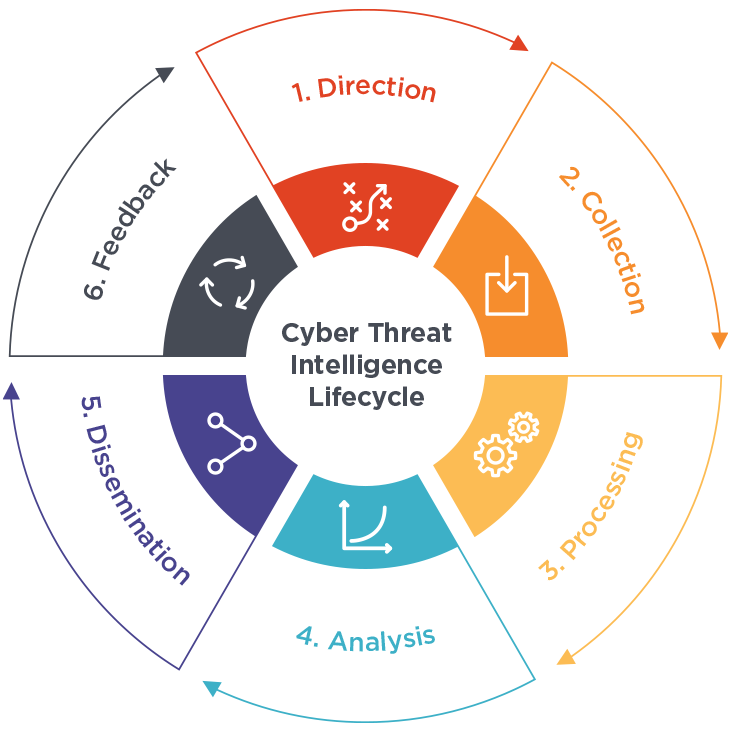

With the PIRs ready to go, you are done planning and now have a direction to work towards. You now have to figure out how to gather the information, process, analysis, disseminate and finally receive feedback on it—in other words, figure out how to work them into the intelligence life cycle. My next post in this blog series will be working with the intelligence life cycle.

Resources

The three post i’ve alredy discuses were:

You do need to sign up for a maliling list for Intel 471’s handbook, but I believe it to be worth it.

One last resource I wanted to provide Is how PIRs and Risk can come together:

The Death of Private Sector Priority Intelligence Requirements By Levi Gundert and Stu Solomon